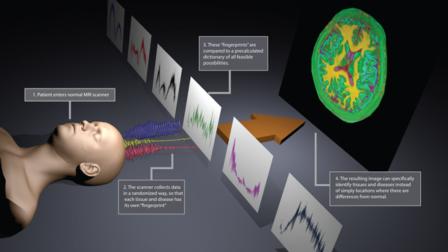

A new method of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) could routinely spot specific cancers, multiple sclerosis, heart disease and other maladies early, when they are most treatable, researchers at Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals (UH) Case Medical Center suggested in the journal Nature.

Each body tissue and disease has a unique fingerprint that can be used to quickly diagnose problems, the researchers said.

By using new MRI technologies to scan for different physical properties simultaneously, the team differentiated white matter from gray matter from cerebrospinal fluid in the brain in about 12 seconds, with the promise of doing this much faster in the near future, according to a release.

The technology has the potential to make an MRI scan standard procedure in annual check-ups, and a full-body scan lasting just minutes would provide far more information and ease interpretation of the data, making diagnostics cheap compared to today’s scans, they stated.

“The overall goal is to specifically identify individual tissues and diseases, to hopefully see things and quantify things before they become a problem,” said Mark Griswold, a radiology professor at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine. “But to try to get there, we have had to give up everything we knew about the MRI and start over.”

Griswold has been working on this goal with Case Western Reserve’s Vikas Gulani, an assistant professor of radiology, and Nicole Seiberlich, assistant professor of biomedical engineering, for a decade. During the last three years, they developed the technology and proved the concept with graduate student Dan Ma Kecheng Liu, collaborations manager from Siemens Medical Solutions Jeffrey L Sunshine, professor of radiology and a radiologist at UH Case Medical Center, and Jeffrey L Duerk, dean of Case School of Engineering and professor of biomedical engineering.

A magnetic resonance imager uses a magnetic field and pulses of radio waves to create images of the body’s tissues and structures. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting (MRF) can obtain much more information with each measurement than a traditional MRI.

“With an MRF,” Griswold said, “we hope that with one step we can tell the severity and exactly what’s happening in that area.”

Other researchers have tried to use multiple parameters in MRI’s, but this group was able to scan fast and with higher sensitivity than in previous attempts, he continued. “This research gives us hope. We can see that it is possible the MRI can see all sorts of things.”

The group expects to reduce scanning time and continue to collect a library of fingerprints, over the next few years.

Case Western Reserve and UH Case Medical Center have a 31-year history of developing MRI technology with Siemens. The MRI manufacturer and National Institutes of Health supported the research.